Painfully Funny. Humour in the Films by Paul Verhoeven and Alex Van Warmerdam

Paul Verhoeven and Alex van Warmerdam, the masters of Dutch cinema, use humour at the cutting edge. Their most recent films prove this: Benedetta and Nr. 10. Whereas Verhoeven often uses satire and hyperbole, Van Warmerdam is the king of absurdism and understatement.

There he was: curled up in his sleeping bag around the toilet bowl in which a truck driver was pissing. Stranded at a petrol station on the Danish border because no one wanted to give him and his friend a lift at night. And it had started so beautifully, their hitchhiking adventure in the early 1970s on the way to the Valhalla of the porno industry at the time: as a dream of the free and easy Danish girls they would chat up.

It could have been a comic scene from one of his films, but this anecdote is (see a Dutch daily Volkskrant interview from 2016) taken from the life of filmmaker Alex van Warmerdam (b. 1952). High expectations that collide with a deeply disappointing reality: it’s so funny you could cry.

In his latest film Nr. 10, about Günter (Tom Dewispelaere), a man who was once found as a child in a forest, Van Warmerdam continuously plays with the tension between those two extremes, with comic effect. Highly placed persons show interest in Günter’s life. He feels flattered by that. Until their true intentions come to light and their interest turns out not to be in him, but in his daughter.

In Nr. 10 (2021), one reality after another keeps on piling up like this, as we learn more and more about the characters and the figures who drive them behind the scenes. Those in control also appear to be controlled in turn, with each layer having its own hidden agenda: a comical stacking of ever-changing perspectives, which is carried through to the absurd. In addition, van Warmerdam also pokes fun at genre laws. The result is a film that you could call a genre comedy about perspective, but that can also be described as a film about the belief in a certain reality.

Mud, shit

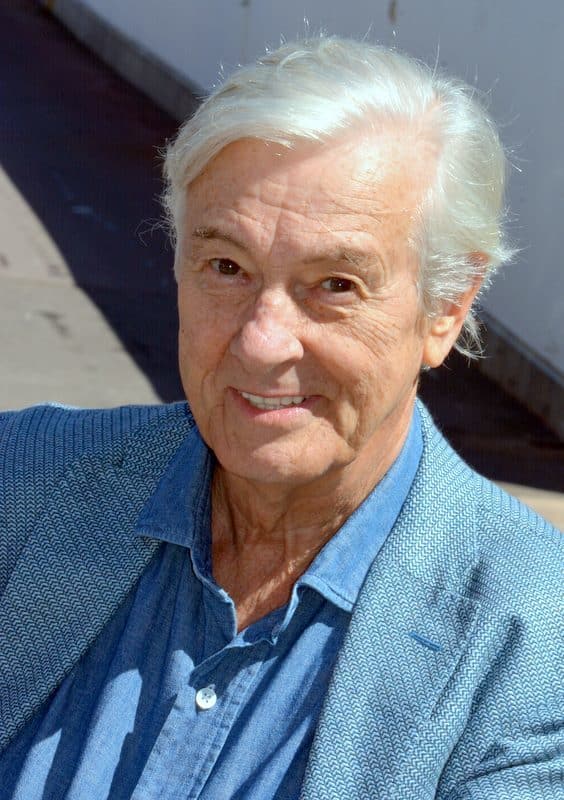

Paul Verhoeven

Paul Verhoeven© Georges Biard - Wikimedia Commons

Paul Verhoeven (b. 1938), the other grandmaster of contemporary Dutch cinema, plays in a similar way with seemingly incompatible extremes. As a young man, he too experienced first-hand how the adventurous dream of the future and banal reality are intertwined and how humour offers a way out of the tension between the two. In his biography, he tells how King Kong seemed to detach himself from the silver screen during a visit to the cinema to throw himself at him as an angel of vengeance sent by God. Verhoeven had just decided with his girlfriend that her unplanned pregnancy would end in an abortion, a procedure that was still illegal in the late 1960s. The worries about this plus the stress about his dreamed future as a filmmaker, which he saw shattered by the inherently difficult process of seeking finance, led to a short circuit in his head.

On the rebound, in his later work, Verhoeven sought guidance in tangible realism that others often brush aside: mud, shit, intestines, semen, blood. The naked truth, so to speak, that hurts your eyes, but that also tickles your funny bone by laying it on so thick.

Verhoeven looks for something to hold on to in the naked truth: it hurts your eyes, but also tickles your funny bone

Benedetta (2021) is about a medieval nun who, thanks to her visions, is put in charge of an Italian monastery and whose luxurious position allows her to embark on a forbidden relationship with another woman. In that film, Verhoeven has the mutually attracted girls sit together on a crapper. As if that wasn’t earthy enough, the free-spirited newcomer Bartolomea farts. ‘Ah delicious!’, she shouts. The primly raised Benedetta, accustomed to the sacred silence of the monastery, snarls at her: ‘Ssht! No noise!’ Bartolomea, responds unperturbed: ‘A fart. That’s allowed, I hope, isn’t it?’ That fart in the bowels of a monastery, as a naughty dissonance in a romantically charged scene; it’s like a double dose of swearing in the church. Verhoeven defies the expectations of his audience by desecrating a convention with something unheard of. Exactly the kind of anarchic humour in which Verhoeven takes pleasure.

An anarchist in the monastery

Although both operate in the same field of tension, the way Verhoeven and van Warmerdam tickle the funny bone is quite different. Whereas Van Warmerdam is the master of understatement, Verhoeven goes for exaggeration. Whereas Van Warmerdam exposes the absurdism in the everyday things of life in a deadpan way, Verhoeven’s films are often satires in which the hyperbole is blown up to practically metaphorical proportions.

Take the opening scene of Benedetta, in which we see how the leading lady travels by carriage with her well-to-do family to the nunnery in Pescia as a young girl. Along the way, the party is ambushed by a bunch of dangerous-looking mercenaries on horseback. When they take away the girl’s silver necklace, she threatens them with the wrath of God that will descend upon them if they do not immediately return the jewellery piece to her. At that moment, a passing bird poops smack dab on the head of one of the bandits. The girl immediately claims it as a sign of the Lord. Just like the viewer, the robbers see the humour in that. More out of respect for her guts than out of fear of God, she gets her necklace back from them.

A fart in a monastery: exactly the anarchic humour in which Verhoeven takes pleasure

The scene contains much of what will come back later in the film: the tension between the sacred and the earthly, between chance and theatre, being visionary and daring to bluff. Benedetta is a film that mocks monastic life by inflating inconsistencies and condensing them to an almost comic strip-like essence. Where Benedetta’s delusions of grandeur induced by faith are still laughed off as childlike fantasy in the opening scene, her visions as an adult have become a game of truth or dare on life and death. Benedetta is an anarchist who knows how to bend the rules of the game to her will. Verhoeven challenges the viewer to take that as a metaphor for the effectiveness of monastic life and to see the humour in it.

Platitude in the wrong place

Van Warmerdam is often at his funniest when apparently nothing happens. Or when adults pester each other like touchy, offensive children. However, having his actors act funny is out of the question for him. The humour is in their static nature, their rigid inflexibility. His black comedy humour is rooted in understatement. But here, too, the process of laying it on thick evokes an almost comic book-like essence.

Van Warmerdam is at his funniest when apparently nothing happens

An example from Nr. 10 is the recurring static shot of four people in a car, seen from the bonnet, on their way to a theatre rehearsal. It’s three actors and a driver. Where you expect animated conversations between colleagues on the way to the workplace, you look at four people sitting motionless in a car, barely exchanging a word. Their blank faces and nondescript clothing take on something menacing: they sit there like a bunch of criminals on their way to a liquidation. Van Warmerdam plays with this genre cliché of four silent people in a car, borrowed from German krimi films. A deboned platitude in the wrong place: that makes us laugh.

Still from 'Nr. 10' by Alex van Warmerdam. A deboned platitude in the wrong place: that makes us laugh.

Still from 'Nr. 10' by Alex van Warmerdam. A deboned platitude in the wrong place: that makes us laugh.The limits of what is acceptable

Alex van Warmerdam

Alex van WarmerdamThe intransigence of Van Warmerdam’s characters also resounds when they deny the obvious. For example, when Günter’s girlfriend at the breakfast table says to him: ‘You’re not here.’ She means it figuratively: that he is elsewhere in his mind. But because Günter agrees with a simple ‘yes’, Van Warmerdam subtly emphasizes the literal meaning of her observation. And then it becomes funny, because they both claim that he is not there, while we see that he really is there. This is another relatively innocuous pun that challenges the viewer to wonder if he prefers to believe the character or his own eyes instead.

In every Warmerdam film, there is a moment when something suddenly happens that exceeds the limits of what is acceptable. An outburst of violence so gross and out of all proportion that it turns into slapstick with Van Warmerdam seemingly wanting to wipe the smile off your face at a single stroke. In Nr. 10, it’s the moment when Günter, at the premiere, casually rams a nail into the foot of his rival – fellow actor Marius (Pierre Bokma) – from the prompter’s box. Emblematic comic book violence, which leaves the viewer confused: funny yes, but also particularly painful.

Humour detaches itself from good and evil, overturns the norm and thus creates a new reality

Humour that takes place on the cutting edge is the most interesting. It exploits the shock of the violation of good morals, good taste, of kicking a sacred cow. The shocking moment, the provocation goes hand in hand with liberating laughter. Humour detaches itself from good and evil, overturns the norm and thus creates a new reality. Humour is anarchic, creative, and ambiguous. The prim and proper corset is taken off. The space given to misbehaviour is liberating. Humour is playful, toys with the normal course of events; turns it into a dance. It is an exercise in flexibility, with a mind-expanding effect.

The naked truth

It is no coincidence that sex and religion, with their emotionally charged status, are perhaps the most rewarding subjects of ridicule for both Verhoeven and Van Warmerdam. Because religion with its – already absurd – absolute claim to having “the truth” and its strict hierarchy and rituals seems at its core incompatible with the relativizing, creative power of humour. And sex – well: besides being the most passionate and exalted taboo subject arousing everyone’s interests, isn’t that also the most vulnerable, ridiculous, bestial feature of mankind?

It is no coincidence that sex and religion are perhaps the most rewarding subjects of ridicule for both Verhoeven and Van Warmerdam

Verhoeven already proved that the naked truth tickles the funny bone in De Vierde man (The Fourth Man, 1983), in which writer Gerard Reve (Jeroen Krabbé), possessed by desire, throws himself on the statue of Christ in a church, which he takes to be his beloved Herman (Thom Hoffman). He tries in vain to strip the statue of its implacable wooden loincloth.

Still from 'De Vierde Man' (The Fourth Man, 1983) by Paul Verhoeven

Still from 'De Vierde Man' (The Fourth Man, 1983) by Paul VerhoevenIn Benedetta, Verhoeven comes up with a new variation on this scene, when Benedetta – who has been the “bride of Jesus” ever since her entry into the monastery – turns to him in raptures in a vision. This time the loincloth of the living Jesus on the crotch does give, but he appears to have the sexless torso of a mannequin. Since the love of Jesus turns out to be purely platonic, Benedetta takes that as permission to seek physical satisfaction from Bartolomea. A great joke that does exactly what humour can do: defy boundaries. It is satire at its sharpest: mockery that confuses the viewer. An invitation to laugh as a secret pleasure.

Still from Benedetta by Paul Verhoeven

Still from Benedetta by Paul Verhoeven© Guy Ferrandis

In Van Warmerdam’s Nr. 10

as well, the church is seen as an institution that deals in articles of faith. After all, the Catholics want, as Günter puts it, ‘to talk a healthy person into a disease in order to be able to sell him a medicine’. The cure for the guilt is Jesus, the praises of which are even sung on an interplanetary scale by the church. The final scene in Van Warmerdam’s film is a statue of Mary with the baby Jesus on her arm, floating in space. A beautiful counterpart to the young Van Warmerdam, dreaming of Danish girls, lying under a toilet bowl. Both scenes illustrate how relative the belief in a certain reality is as soon as circumstances and thus perspective change. This is how you dream; that’s how you are lying under a toilet bowl. While the statue of Mary may be considered sacred in a church setting, it becomes a pointless thing when floating in space by lack of devotees. Both examples show a sense of perspective, a sense of humour, which will become increasingly rare the less room is left for alternative visions outside of official truth.

Still from 'Nr. 10' by Alex van Warmerdam.

Still from 'Nr. 10' by Alex van Warmerdam.Is that funny? And is it even meant to be that way? According to Van Warmerdam, there is no way to predict the public’s sense of humour. Sometimes a joke doesn’t work at all. But there can also be too much laughter. That reality often turns out crazier than expected, as he experienced forty-five years after having landed under a toilet bowl again at the premiere of Schneider vs. Bax (2015). In a scene in which one of the characters claims to have stabbed someone else to death, the audience chuckled. Van Warmerdam: ‘Completely insane’.